If it comes to the psychology of pricing and questions about how to prepare offers, the first sentence (unfortunately) must be: The price cannot trigger anything. It will only then become effective if the purchase intention already exists. Or, put in a nutshell: If it were so simple, everybody could do it.

Regarding price tolerance, differences in prices have nearly no effect on the purchase decision. For pricing, first of all, the question is important, whether it is about a product or a service that is bought frequently or not. For products that are bought more frequently, customers have kind of a »reference price« in their mind (learnt, but not necessarily conscious basis for orientation for the estimation of prices). This reference price lies within a certain tolerance range, within which a price can be without being estimated as too high or too low. Within the price tolerance, differences in prices have nearly no effect on the purchase decision.

If a price is significantly outside of the tolerance range, customers lose interest: If a product, for which a reference price exists, is estimated as being too expensive, the heuristics »expensive = good« remain effectless, so the price »tilts« out of the price tolerance as well. “The price is not an issue.” does actually mean: “It’s perfectly fine if the product is a bit more expensive.” By implication that means that partners and customers will become suspicious, if the price is remarkably low. A low price might be perceived as a sign of low quality and maybe also of the low trustworthiness of the vendor.

The more expensive a performance or product is, the less is saved: In general, people tend to save money. Paradoxically, this willingness decreases with a rising price. Whereas the prices of toothpastes are compared and money is saved on that basis, people tolerate higher prices for furniture, for example. Only a very low tendency to save money by price comparison can be determined for the purchase of cars. Principally, the following applies: The more expensive a product the lower the effect of bargains. Thus, it can be assumed that the comparison of prices has in particular an influence on the purchase probability for standard products, not or nearly not for special products.

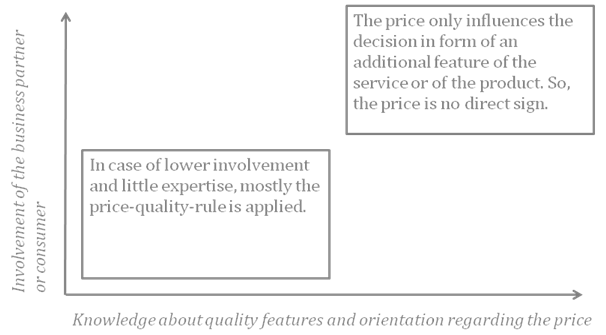

The involvement of the customer and the knowledge of the same are crucial: If the degree of involvement (= intrinsic commitment for a purchase decision) is looked at in relation with the knowledge about the product, an interesting system emerges:

If the purchase means little to the customer and he or she has only little knowledge, then often the rule »expensive = good« will be applied. So, the price becomes a direct sign for quality. That differs if the purchase means a lot to the customer (high involvement) and he or she has thoroughly gathered information about the product and the product category. Then the price loses its symbolic character and becomes one feature among many others. The importance of the price is relativized in comparison with other features and the price becomes to one factor of the total utility.

Therefore, for the preparation of offers and possible later negotiations, it is important, whether the customer or business partner has inquired the product or the service several times and has a reference price due to this. If it is not about standard products, but about more or less special services, it can be assumed that the customer does not have a reference price. In such cases, the price tolerance remains undetermined or at least very large. Furthermore, the »intrinsic involvement« of the customer is crucial. If it is high, it can be assumed that the price does not play a major role, but only one among many.

In a nutshell, the price does by far not play the role often assigned to it in discussions. Other factors play – at least for non-standardized products and services, which represent by far the bigger part – a significantly bigger role, for example the relationship between the potential business partner (or the ability to establish a relationship) and the presence of positively definable USPs. The answer to the question, why a certain product can be realized especially with me is thus much more important for the most companies or offers than the price. (As already mentioned: That all can only be applied in exceptional cases for standardized products or services.)

Is it true that those things are good which are expensive? The connection »expensive = good« especially exists in the heads of customers, but it does not necessarily exist in the real world of products. Price and quality do indeed only correlate in some cases; in many other cases the correlation is zero or even negative (products of poor quality with high prices).

It’s about status – if I can’t afford something, it will become more attractive: The willingness to purchase expensive products depends on the social status of the buyer (expensive products as status symbols). People with a higher income perceive prices in a different way than people with a low income. For the latter, a product may seem the more valuable and prestigious the less »achievable« it is. Above that, the willingness to pay higher prices or to prefer lower ones depends on the attitude of the consumer. If the purchase of a certain product seems to be »flamboyant« or »inappropriate« regarding the value system of a certain target group, this will lead to the rejection of the product.

Where the journey takes us

The topic discussed here gets even more interesting when it is looked at in the background of the current »great developments«:

According to Peter Drucker, industry is experiencing the same what happened to agriculture already a long time ago – an increase of productivity with a heavily falling number of employees at the same time. The present is already mainly characterized by services, the problem, however, is, Drucker said, that our central instruments such as planning and accounting were based on models of industrial logic. We have transferred those models to services, even public administration, without being able to assign cash flows to the performances. The input and the output are known and the reason for spending money, but money and performance cannot reasonably be matched.

Interesting conclusions can be drawn, if Drucker’s considerations are combined with a model of the organizational psychologist Edgar Schein and if that is transferred to the relationship between service providers and their customers. Just like management consultants used to help their customers solving current, mostly complex tasks, today the most service providers (and many manufacturers as well) are busy helping their clients.

According to Schein, there are three kinds of such help:

Mode 1 – Specialist’s help: The customer does not only know that he has a problem, but he exactly knows which kind of problem he has. He can describe it in detail and knows the appropriate solution. The customer contacts an appropriate specialist and buys the solution there. So, if a standard software with some specific customizations for seven workstations is needed for the accomplishment of standard tasks, then this is a typical case of specialist’s help.

Mode 2 – The doctor-patient relationship: In this case the customer knows that there is a problem, but maybe he’s not quite sure what to do about it. Here too, the customer contacts specialists, who, however, not immediately offer the solution, but who will make a »diagnosis« which represents the basis for the later solution.

Mode 3 – Consulting and the search for solutions as process: In this third version, neither the customer nor the supplier knows the exact nature of the problem, not to mention the solution. The starting situation is so complex that only a collaborative process of search, analysis and development will lead to the solution. The basis of this process is the (helpful) relationship between the people involved.

Our current company-related thinking models come, for the most part, from industry, and the familiar mode of cooperation between business partners is that of specialist’s help, sometimes maybe also the doctor-patient relationship. Starting situations, however, are so complex at the moment that customers often don’t know what their problem actually is. Software developers know about that and advertising agencies, too. One solution scenario in the field of IT is not to prepare comprehensive requirements catalogues any more, but to develop the software step by step in a continuous dialog with the customer (Scrum). Larger ad agencies often open small offices within the premises of their customers. Nowadays, the customers even have to be involved in preparing offers as the demand analysis has become a process that can nearly not be divided into standardizable stages any more.

In summary, explanations on the current developments indicate a more intensified process character of business processes and set (among others, especially service providers) companies the task to work in even smaller steps and more process-oriented, leading to high demands regarding the ability for dialogues and consulting, and requiring, in particular at the beginning of projects, to ask the right questions and to take the time for necessary clarifications.

Finally, some information on numbers:

First, one question of pricing concerns visual effects – so called »broken prices«, that means amounts directly below a round price (EUR 199 instead of EUR 200) are perceived as lower and thus more favorable. The same goes for the numerical sequence of the price – decreasing numerical sequences are perceived as more favorable than increasing sequences (EUR 531 vs. EUR 479). Above this, the size of the representation of the numbers influences the assessment of the price (the larger the numbers are displayed the more favorable the price is percieved). In addition, a remark on the role of colours: Many supermarkets use several colours for labeling. The fact of a price printed on paper which is connected with »favorable« leads to significant sales increases, no matter if the price is indeed lower than normal.

Second, the so called »anchoring effect« is to be taken into consideration, which means that people’s ability to assess relations correctly is limited after a first »anchor of perception« has been set. This holds true for many kinds of assessments or value judgments. The effect of numbers, however, is especially strong. In practice, that means: If the district attorney urges a high sentence, the defending lawyer’s claim and the sentence will be higher, too, than it would be in case of lower claims. Thus, the first-mentioned number »drags« all numbers thought of and stated afterwards in its direction, that’s an effect which is in particular useful for fee negotiations. Third, a certain »tendency to the middle« shall be assumed. If there are three equipment versions (e.g. premium, comfort and basic), the decision is especially often made in favor of the intermediate version.

This article is also available in German.

Literature:

Bauer, F. (2000): Die Psychologie der Preisstruktur. Entwicklung der “Entscheidungspsychologischen Preisstrukturgestaltung” zur Erklärung und Vorhersage nicht-normativer Einflüsse der Preisstruktur auf die Kaufentscheidung. München: CS Press.

Drucker, Peter F. (2007): Managing in the next society. Classic Drucker Collection. Oxford: Elsevier/Butterworth-Heinemann.

Felser, Georg (2007): Werbe- und Konsumentenpsychologie. 3. Aufl. Berlin, Heidelberg: Spektrum.

Heidig, Jörg; Kleinert, Kim Oliver; Dralle, Thorsten; Vogt, Marianne (2012): Prozesspsychologie. Wie Prozesse, menschliche Faktoren und Wissen im Unternehmensgeschehen zusammenwirken. Bergisch Gladbach: EHP Edition Humanistische Psychologie.

Schein, Edgar H. (2009): Führung und Veränderungsmanagement. Bergisch Gladbach: EHP (EHP-Organisation).

Schein, Edgar H. (2010): Prozessberatung für die Organisation der Zukunft. Der Aufbau einer helfenden Beziehung. 3. Aufl. Bergisch Gladbach: EHP (EHP Organisation).